Earlier this month we celebrated the completion of our USAC-BCulinary Club course with a sensational wine-tasting session guided by Pilar Garcia-Granero — wine expert, teacher, Director of the Escuela Navarra de Cata, former president of the Regulatory Board of the Denominación de Origen (D.O.) Navarra and technical coordinator of the Basque Culinary Center’s Máster en Sumillería y Enomarketing.

I think it’s safe to say that as a group, we were completely captivated by Pilar’s ability to verbalize the layers of flavor contained in our glasses. She encouraged us to recognize and classify our tasting sensations as she masterfully and elegantly led by example — swirling, smelling, swishing, sipping, savoring….

First we tasted my favorite beverage from this region: traditional Basque cider. Sagardoa (in Basque), or sidra (in Castillian Spanish), has a low alcohol content (4-6%) and is produced through the natural fermentation, with no added sugars or flavors, of the juices pressed from a variety of native apples.

Varieties of apples used to make traditional Basque cider, at the Basque Cider Museum – Sagardoetxea

Pilar explained that the apple varieties are selected to carefully balance the final product’s characteristic flavor profile – dry, tart, fresh, vaguely musty, gently fruity, with tones of apple and citrus, and ever so slightly tannin.

Our cider was produced by the cider house Zapiain in Astigarraga, a town at the heart of the Basque cider-making tradition and home to numerous traditional cider houses, or sagardotegia, as well as the fantastic Basque Cider Museum – Sagardoetxea.

Learning to make cider at the Sagardoetxea

Pilar showed us how to examine the cider visually in the bottle, observing its characteristic cloudiness and bits of natural sediment, as well as in the glass, noting the golden yellow tones, the opacity, the slight carbonation. She reminded us that if cider is left in the glass without being consumed in the proper “all-at-once” fashion, the color deepens as the cider oxidizes and loses its fresh flavor.

She demonstrated the distinctive cider pour (a thin stream from a height of at least 20 cm and up to a meter) into the appropriate glass (not a wine glass, but a tumbler, typically 12 cm tall and 9 cm wide across the mouth).

Traditional Basque cider pour; photo from www.seaslugandtheturtle.blogspot

Pliar explained the history of the Txotx, the dramatic tasting ritual of the cider houses during the cider season. From January to April, when the previous year’s cider is ready to be consumed, cider is poured at intervals, when “Txotx!” is called, straight out of the barrels known as kupela.

Txotx! Photo by Jon Urbe, www.argia.com

Historically cider houses did not serve food, they simply opened their doors to buyers to offer tastings of cider before it was bottled. Buyers would bring their own food items to accompany the cider — walnuts and cheeses, simple salt cod dishes, and, if the cider house was equipped, large cuts of meat and fresh, whole fish to cook over a parrilla, or grill.

Idiazabal cheese, sweet quince paste and walnuts on a cider-house table; photo from http://www.sabrosia.com/

Eventually the cider houses recognized their opportunity — they conditioned their kitchens, built out their dining halls, and began to offer what is now the celebrated, traditional cider-house meal: a tender salt cod tortilla (omelette), salt cod with sweet green and red peppers and onions, or salt cod al pil pil, an enormous grilled txuletón (aged rib-eye steak) or a whole, grilled fish, and dessert of whole walnuts, Idiazabal cheese and quince paste.

Enormous steaks awaiting their turn on the grill at Petritegi; photo from http://www.euskoguide.com/

After the cider, we tasted a white txakoli (pronounced “cha-ko-li”) wine, a Getariako Txakolina, D.O., the most widely known type of txakoli.

The majority of Getariako Txakolina is produced in the coastal towns of Getaria and Zarautz in the Basque province of Gipuzkoa, and there are several vineyards scattered throughout the nearby mountains.

La Ruta del Txakoli – The Route of Txakoli; click the image to link to an interactive map of Txakoli vineyards, presented by the Regulatory Board of the Getariako Txakolina Denominación de Origen

Pliar explained that here in Gipuzkoa, nearly all txakolis are made from the Hondarrabi Zuri grape, a white grape resulting in a crisp, tart, slightly sparkling wine with a pale greenish-yellow color and a moderate alcohol content (9.5-11.5%).

Hondarribi Zuri grapes; photo from www.viveroslucea.com.

We learned that there is also a lesser-known red txakoli grape variety in Gipuzkoa, known as Hondarribi Beltza, from which a relatively tiny amount of wine is produced, and that in the Basque province of Bizkaia (Biscay in English), there is a type of txakoli produced from a mix of both red and white grapes. Txakoli wines are also produced on a small scale in the Basque province of Araba/Álava and in the province of Burgos.

Hondarribi Beltza grapes, photo from www.viveroslucea.com

People usually drink txakoli as an apéritif, before a meal, and often while taking part in a txikiteo (also known as a poteo) — the custom of going from bar to bar with friends, usually in the early evening, to drink small glasses of wine or cider (referred to as txikitos or potes), or small glasses of beer (zuritos), accompanied by small appetizers known as pintxos (in the Basque Country) or as tapas (throughout Spain).

Txakoli and pintxos; photo by Borja from “Pintxo Poteo por el Casco Viejo Bilbaino”

Pilar pointed out that the aromas of our txakoli, immediately after being poured into the glass, were reminiscent of green apples, yet once the wine was agitated and aerated in the glass, the aromas expanded, evoking sweet, golden apples. This wine was a big hit with our group!

Next we sampled a pair of Rioja wines made from Tempranillo grapes, the predominant grape of the Rioja region to the south of (and slightly overlapping with, in the province of Álava) the Basque Country.

Map of the Rioja wine regions; image from http://www.riojawine.com

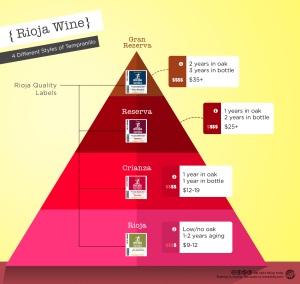

Pilar talked about the four major Rioja wine styles (Rioja, Crianza, Rioja Reserva and Rioja Gran Reserva), their technical definitions and their overall characteristics. This Wine Folly piece also does a great job.

Rioja wine styles defined and average prices in US$; image from www.winefolly.com

First we sampled a young Rioja wine, characteristically aged under two years, with little or no time in oak barrels, and with a relatively high alcohol content of 13.5%.

Thin, fresh and fruity, young Rioja wine is typically enjoyed as a pre-meal apéritif. Traditionally these wines were labelled as vino joven (young wine), though most present-day winemakers label them simply as Rioja.

We moved on to a satistfying Crianza. The Spanish word crianza has several meanings: it can refer to the upbringing, nourishment and education of children, to the breeding, care and nourishment of animals, and to the aging and maturing of wines. While vinos jovenes, or young wines, are sometimes referred to as sin crianza, Crianza wines are by definition aged for a minimum of two years, including at least one year in oak barrels, and have an alcohol content of 13-14%.

After our guided tasting with Pilar, we continued our session by exploring how our wines and cider paired with the various components of our pica-pica spread: cured anchovies, olives stuffed with anchovies, guindillas de Ibarra, semi-cured Idiazabal sheep’s milk cheeses (smoked and unsmoked), Cabrales cheese (a rich blue cheese made from cow’s and sheep’s milks), raw local oak forest honey, dulce de membrillo (sweet quince paste), bonito tuna with olive oil, walnuts and almonds, pa amb tomàquet.

Some stand-out, classic pairings we enjoyed: txakoli with anchovies and with bonito; Rioja and Crianza with our cheeses, cider with nuts, quince paste, Idiazabal cheese…and a bit of everything with everything!

To cap off our evening, students were awarded their certificates for completion of the course. Well done, everyone! Glasses raised to you all! Chin-chin! Zorionak!